On This Page:

ADHD mood swings can be characterized as swift and unexpected mood alterations (either positive or negative) in reaction to environmental stimuli, events, and/or people.

They tend to be shorter in duration than in other conditions, e.g., bipolar mood swings and can happen both repeatedly and frequently.

People with ADHD can indeed experience and feel more intense mood swings when compared to neurotypical individuals and it makes it one of the key hallmark symptoms of the condition.

There are a few reasons why ADHD mood swings can be rather intense and they mostly link back to other associated symptoms.

Emotional dysregulation is a big challenge for many ADHD people, making it difficult for them to manage their feelings and reactions to a vast array of situations and circumstances (Shaw, Stringaris, Nigg & Leibenluft, 2014).

This, coupled with impulsive tendencies (Winstanley, Eagle & Robbins, 2006) and heightened quick reactivity, increase challenges around mood swings and intense emotional expressions.

Heightened sensitivity also makes mood swings more intense, as it increases experiences of environmental stimuli contributing to people expressing intense emotions, e.g., at the office due to noise pollution (Panagiotidi, Overton & Stafford, 2018).

Lastly, other secondary symptoms such as poor organization, time management, and task switching can increase irritability, feelings of overwhelm, and overall life stress, further amplifying mood swing intensity.

What are the Signs of ADHD Mood Swings?

There are several different ways in which ADHD mood swings can manifest, but some commonalities in signs do exist:

- Quick fluctuations in emotions leading to frequent outbursts, e.g., impulsive expressions, rapid changes in feelings, and overreactions.

- Feeling overstimulated in certain situations on environments.

- Frequent changes in plans as a direct result of experiencing a mood swing and wishing to either cancel or make alterations to what was agreed.

- Irritability, such as having a low frustration tolerance, inability to wait, and/or quick decline of mood if things do not go as originally planned.

- Challenges in managing such frustrations potentially leading to further aggravations or even conflicts.

- Experiencing periods of high energy that can last for a few hours.

- Having more intense emotions such as heightened excitability or meltdowns. These can fall on either end of the scale, with both positive and negative emotional signs being present (you do not need to have only one type).

What do ADHD Mood Swings Feel Like?

People may either switch emotions entirely, e.g., from being happy to sad, very quickly, or they can have rapid changes in intensity, e.g., from annoyed to very angry. It can also be challenging to regain emotional stability following a mood swing.

Alice described her personal experience with this as “Sometimes you wake up and you’re on top of the world, and only one thing happens which is actually quite small, and suddenly you’re down as hell” (Schrevel, Dedding, van Aken & Broerse, 2016).

As these changes can be so quick and frequent, this can lead to feelings of stress, overwhelm, and being unable to control your own body, especially in relation to impulsive decisions that directly result from a mood swing.

Frustration over the situation is common, coupled with exhaustion both emotionally and mentally.

What Can Cause Mood Swings in ADHD?

ADHD mood swings do not have a single attributable cause but they are more of a collection of neurobiological and environmental factors working together to generate and sustain them.

Let us discuss some of the most common causes of mood swings in ADHD:

Heightened emotional response

Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) is a heightened emotional response and reaction to a situation that oftentimes may be disproportionate to what has caused it.

For example, your partner has taken a bit longer to do a task you asked and as a result, you got very angry and lashed out at them.

Such struggles with emotional dysregulation are common symptoms within the ADHD population (Shaw, Stringaris, Nigg & Leibenluft, 2014), with RSD further amplifying the emotional impact of criticisms and overall decreasing well-being.

Difficulty focusing

Difficulty focusing is commonly shared among people with ADHD (Barkley, 1997) and often leads to challenges in paying or maintaining attention, leading to mood swings.

For example, trouble focusing during a lecture can quickly lead to feelings of intense frustration. Those can dissipate just as quickly as they have risen soon as the lecture is done and the cause of frustration has ended.

This constant shift in focus and inability to stay on track may also trigger feelings of overwhelm and stress, resulting in mood fluctuations.

Constantly being unable to focus when required can also lead to frustration with one’s self-perception and personal capabilities. This could make someone with ADHD frequently feel lower moods.

Feeling ‘different’

People with ADHD can struggle to fit into a neurotypical world, oftentimes feeling different or that they do not belong.

This struggle of assimilating to societal norms and expectations can understandably lead to emotional distress, vulnerability, and intense feelings.

For example, challenges in picking up social cues can make socializing more effortful, leading to mood swings just as sudden feelings of sadness, disappointment, or anger at people.

People with ADHD may use ‘masking’ to avoid coming across as neurodiverse. However, this can become emotionally draining and result in mood changes.

Comorbid conditions

Certain other comorbid conditions (which are additional coexisting conditions alongside ADHD) may also directly impact and result in heightened mood swings due to the combination of symptoms that end up escalating each other.

Some common ones are anxiety disorders (Tannock, 2000), depression (Biederman, 2004), Intermittent Explosive Disorder or IED (Gnanavel, Sharma, Kaushal & Hussain, 2019), and Bipolar Disorder (Nandagopal et al., 2011).

For example, having rejection sensitivity due to ADHD, and feeling upset over receiving criticism, can be amplified by depression, leading to stronger emotions of sadness and negative self-perceptions.

Such conditions often exhibit their own symptoms of mood swings, so cooccurrence increases such emotions further.

Medication

While medication can greatly benefit people with ADHD in managing symptoms, it can also lead to mood swings as part of the medication’s side effects.

Each person is unique in how they react and issues around dosages, other medications the person may be taking, and the time it takes for someone to get used to the medication may increase the chances of mood swings.

Certain neurotransmitter levels may also be affected, such as dopamine (Miller, Thomas, Gerhardt & Glaser, 2013), leading to potential further emotional fluctuations as this chemical can affect mood regulation.

Lastly, medication effects on mood swings can also fluctuate with someone’s age. So children may react differently to medical stimulants compared to adults (Firestone, Musten, Pisterman, Mercer & Bennett, 1998).

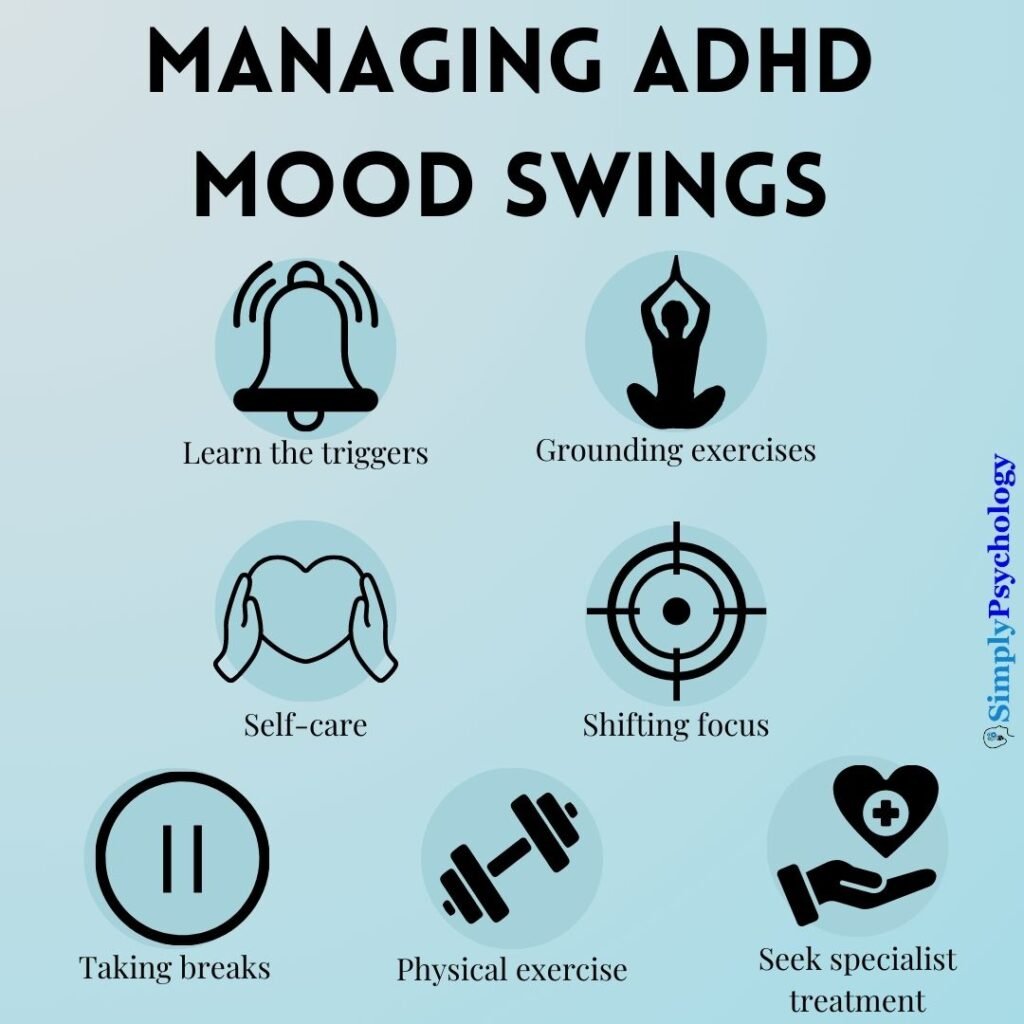

Managing Mood Swings

Learning how to regulate emotions and subsequent actions and behaviors better can, thus, have wide-reaching benefits on someone’s well-being, relationships, and overall life.

Let us discuss a few ways someone with ADHD can manage their mood swings:

Learn the triggers

Learning your triggers is a great starting point in learning how to manage your mood swings, as it can give you guidance on which situations to apply coping strategies, which to avoid entirely if possible, and which ones are more manageable.

Ways you can begin to explore this are:

- Keeping a journal and documenting any mood swings and when they happen

- Asking trusted relatives, friends, or loved ones for their perspectives and when they have noticed emotional fluctuations

- Using technology such as mood-tracking apps to monitor your moods

- Label the feeling

By labeling the feeling you are taking a step back from the emotionality of the situation and trying to use more conscious rational thinking in explaining how you feel.

You can think of it as zooming out and looking at the bigger picture of the situation instead of just focusing on the isolated instance of the mood swings.

Increasing emotional awareness may take time and practice but in the long run, it can help you to manage further mood escalations and impulsive decision-making.

Feel free to keep a journal with all your reflections, as it can help you look back and see your progress as well.

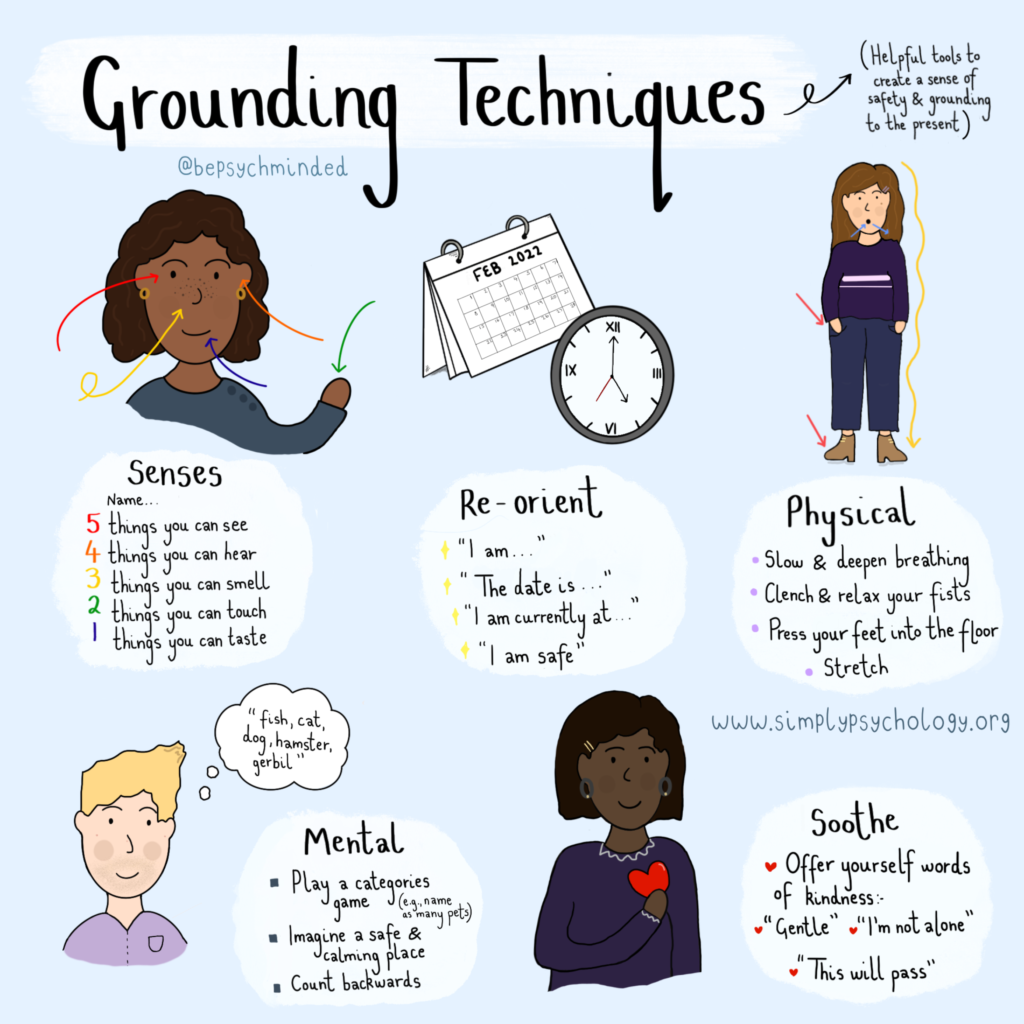

Grounding exercises

Grounding exercises are another great way to help you become more aware and present in the current moment, which can help diffuse intense emotions (Bueno et al., 2015). Examples of such exercises include controlled breathing, meditation, and mindfulness activities.

Because individuals with ADHD have a tendency towards hyperactivity, it can be beneficial to engage in activities that promote stillness. This allows you to redirect your attention to grounding activities that bring you into the present moment, such as art.

However, since these activities may be unfamiliar to many, it is important to give them a fair chance and not give up after just one attempt. It is recommended to try them multiple times before deciding whether or not they work for you.

Self-care and self-compassion

Ensuring you are practicing both self-care and self-compassion is key in ensuring you give yourself the time and space to decompress.

Remind yourself that mood swings are part of ADHD and are a common struggle for many with the condition; you are not isolated nor alone in this experience.

It’s important to remember that mood swings, while they may feel frustrating, are a normal part of life sometimes, and we should not beat ourselves up for experiencing intense emotional reactions.

Identify any self-care activities that feel best for you, e.g., walking, baking, drawing, etc., and show yourself some self-love and understanding.

Your body may also feel very tense during a mood swing, so ensure you take care of yourself physically as well, e.g., with massages to relieve pent-up stress and knotted muscles.

Shifting focus

Shifting focus can help take your attention off of the situation that has led to the mood swing and redirect your energy into something more deescalating instead.

Try and switch your energy to another activity that you typically find stimulating, e.g., a YouTube video, music, a video game, etc.

Move your attention away from why the mood swing has happened and who is to blame. If your emotions have already escalated, ruminating on the situation may only serve to further elevate how you are feeling about what happened.

This does not mean ignoring your emotions completely; only to calm down their intensity in the moment.

Taking breaks

Allowing yourself to take breaks when needed is also part of taking care of yourself and ensuring you give time to calm down and regain emotional stamina.

Try focusing on pleasant activities that lower your stress levels and make you happy. It will look different for everyone, so you can start by making a list of what brings out positive and secure feelings in you.

Feel free to utilize technology as well, such as apps that remind you to take a break, hydrate, or send you motivational quotes throughout the day.

Alternatively, use that time to either do something productive for yourself, decompress, or let your brain relax.

Physical exercise

Physical exercise has overall wonderful benefits for people with ADHD, but it can also be especially helpful to let off steam and unwind from intense emotions (Hoza et al., 2015).

Research has indicated that working out has several benefits in helping us reduce stress, e.g., Tai Chi (Hernandez-Reif, Field & Thimas, 2001), and releases endorphins which can help elevate mood (Ng, Ho, Chan, Yong & Yeo, 2017).

Identify if lower or higher-intensity workouts are the best fit for you, and to get started, you can try some at-home activities first until you find your preference. Consulting a personal trainer is also a good option, especially if you are new to the space of exercising.

Seek specialist treatment

Lastly, speaking to a professional and seeking specialist treatment can help provide further insight into the whys and hows of your mood swings.

Through their guidance, a care plan can be put into place, providing more targeted interventions and further strategies on how to manage mood swings.

Such techniques can focus on various aspects from when the emotions begin to arise, to how to diffuse them and also how to deal with the aftermath as well. The usual treatment routes include therapy, medication, or a combination of both.

FAQs

Can ADHD mood swings lead to weaker impulse control?

ADHD mood swings can certainly lead to weaker impulse control, mainly due to emotional fluctuations.

If someone is more prone to frequently reacting more intensely to situations and struggles with regulating their feelings, this directly impacts their ability to maintain both emotional and behavioral control.

Consequently, actions such as immediate reactivity, rushed decision-making, and poor ability to reflect can arise, which are hallmarks of weaker impulse control.

Can untreated or undiagnosed ADHD lead to mood swings?

If ADHD is left untreated or undiagnosed, this can indeed lead to mood swings. The main cause of this is a lack of symptom management (either medically or therapeutically), which can lead to increased impulsivity, emotional reactivity, and rapid shifts in feelings, thoughts, and behaviors.

Such situations directly feed into mood swings creating a vicious cycle that can start impacting other areas of life like relationships, work, academia, self-perceptions, and personal stress levels.

Additionally, if someone is unaware that they have ADHD, they could be more frustrated with themselves and not understand why they are having all these feelings and frequent fluctuations.

Lastly, research has also indicated that children with undiagnosed ADHD displayed more dysthymia (depressive mood episodes), than those who had been diagnosed (Shekim, Asarnow, Hess, Zaucha & Wheeler, 1990).

This further highlights the importance of correct and timely condition diagnosis, to prevent both the generation and exacerbation of symptoms.

Are ADHD mood swings similar to bipolar disorder?

While ADHD and bipolar disorder do share some similarities in terms of their mood swing presentations, they are both distinct conditions with their own underlying causes and symptoms and should not be misconstrued.

For ADHD, mood swings are more centered around the inability to regulate emotions and manage impulsive behaviors, which are mostly centered around a reaction to a certain situation, stimuli, or stressor (Asherson, Chen, Craddock, & Taylor, 2007).

For bipolar disorder, mood swings are more characterized by episodes (either very low or very high moods), that can last far longer than in ADHD and can occur without a specific stressor (Mansell, Morrison, Reid, Lowens & Tai, 2007).

How can you help someone who is experiencing ADHD mood swings?

If you know someone who is experiencing ADHD mood swings and you would like to help, here are a few ways to support them:

– Try and be both patient and understanding. This will help create a safe space for them and reduce stressors that could have increased mood swings.

– Encourage them where you can to talk about their emotions, and offer quality time to listen. This can open up discussions around self-reflection and what might be triggering to them.

– Educate your own self about ADHD overall, how it can manifest, how symptoms may be exacerbated, and similarly, how they can be managed.

– Encourage them to seek out help from a qualified professional specializing in neurodiverse conditions such as ADHD.

References

Asherson, P., Chen, W., Craddock, B., & Taylor, E. (2007). Adult attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: recognition and treatment in general adult psychiatry. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(1), 4-5.

Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of ADHD. Psychological bulletin, 121(1), 65.

Biederman, J. (2004). Impact of comorbidity in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of clinical Psychiatry, 65, 3-7.

Bueno, V. F., Kozasa, E. H., da Silva, M. A., Alves, T. M., Louzã, M. R., & Pompéia, S. (2015). Mindfulness meditation improves mood, quality of life, and attention in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. BioMed Research International, 2015.

Firestone, P., Musten, L. M., Pisterman, S., Mercer, J., & Bennett, S. (1998). Short-term side effects of stimulant medication are increased in preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 8(1), 13-25.

Gnanavel, S., Sharma, P., Kaushal, P., & Hussain, S. (2019). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity: A review of literature. World journal of clinical cases, 7(17), 2420.

Hernandez-Reif, M., Field, T. M., & Thimas, E. (2001). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Benefits from Tai Chi. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 5(2), 120-123.

Hoza, B., Smith, A. L., Shoulberg, E. K., Linnea, K. S., Dorsch, T. E., Blazo, J. A., … & McCabe, G. P. (2015). A randomized trial examining the effects of aerobic physical activity on attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms in young children. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 43, 655-667.

Mansell, W., Morrison, A. P., Reid, G., Lowens, I., & Tai, S. (2007). The interpretation of, and responses to, changes in internal states: an integrative cognitive model of mood swings and bipolar disorders. Behavioural and Cognitive psychotherapy, 35(5), 515-539.

Miller, E. M., Thomas, T. C., Gerhardt, G. A., & Glaser, P. E. (2013). Dopamine and glutamate interactions in ADHD: implications for the future neuropharmacology of ADHD. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents, 109.

Nandagopal, J. J., Fleck, D. E., Adler, C. M., Mills, N. P., Strakowski, S. M., & DelBello, M. P. (2011). Impulsivity in adolescents with bipolar disorder and/or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and healthy controls as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. Journal of child and adolescent psychopharmacology, 21(5), 465-468.

Ng, Q. X., Ho, C. Y. X., Chan, H. W., Yong, B. Z. J., & Yeo, W. S. (2017). Managing childhood and adolescent attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) with exercise: A systematic review. Complementary therapies in medicine, 34, 123-128.

Panagiotidi, M., Overton, P. G., & Stafford, T. (2018). The relationship between ADHD traits and sensory sensitivity in the general population. Comprehensive psychiatry, 80, 179-185.

Schrevel, S. J., Dedding, C., van Aken, J. A., & Broerse, J. E. (2016). ‘Do I need to become someone else?’A qualitative exploratory study into the experiences and needs of adults with ADHD. Health Expectations, 19(1), 39-48.

Shaw, P., Stringaris, A., Nigg, J., & Leibenluft, E. (2014). Emotion dysregulation in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(3), 276-293.

Shekim, W. O., Asarnow, R. F., Hess, E., Zaucha, K., & Wheeler, N. (1990). A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, residual state. Comprehensive psychiatry, 31(5), 416-425

Tannock, R. (2000). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder with anxiety disorders.

Winstanley, C. A., Eagle, D. M., & Robbins, T. W. (2006). Behavioral models of impulsivity in relation to ADHD: translation between clinical and preclinical studies. Clinical psychology review, 26(4), 379-395.