On This Page:

This type of personality concerns how people respond to stress. However, although its name implies a personality typology, it is more appropriately conceptualized as a trait continuum, with extremes of Type A and Type B individuals on each end.

Type A personality is characterized by a constant feeling of working against the clock and a strong sense of competitiveness.

Individuals with a Type A personality generally experience a higher stress level, hate failure, and find it difficult to stop working, even when they have achieved their goals.

Research Background

Friedman and Rosenman (both cardiologists) actually discovered the Type A behavior by accident after they realized that their waiting-room chairs needed to be reupholstered much sooner than anticipated.

When the upholsterer arrived to do the work, he carefully inspected the chairs and noted that the upholstery had worn in an unusual way: “there’s something different about your patients, I”ve never seen anyone wear out chairs like this.”

Unlike most patients, who wait patiently, the cardiac patients seemed unable to sit in their seats for long and wore out the arms of the chairs. They tended to sit on the edge of the seat and leaped up frequently.

However, the doctors initially dismissed this remark, and it was only five years later that they began their formal research.

Friedman and Rosenman (1976) labeled this behavior Type A personality. They subsequently conduced research to show that people with type A personality run a higher risk of heart disease and high blood pressure than type Bs.

Although originally called “Type A personality” by Friedman and Rosenman it has now been conceptualized as a set of behavioral responses collectively known as Type A behavior Pattern.

Type A Behavior Pattern (TABP)

Competitiveness

Type A individuals tend to be very competitive and self-critical. They strive toward goals without feeling a sense of joy in their efforts or accomplishments.

Interrelated with this is the presence of a significant life imbalance. This is characterized by a high work involvement. Type A individuals are easily ‘wound up’ and tend to overreact. They also tend to have high blood pressure (hypertension).

Time Urgency and Impatience

Type A personalities experience a constant sense of urgency: Type A people seem to be in a constant struggle against the clock.

Often, they quickly become impatient with delays and unproductive time, schedule commitments too tightly, and try to do more than one thing at a time, such as reading while eating or watching television.

Hostility

Type A individuals tend to be easily aroused to anger or hostility, which they may or may not express overtly. Such individuals tend to see the worse in others, displaying anger, envy, and a lack of compassion.

When this behavior is expressed overtly (i.e., physical behavior), it generally involves aggression and possible bullying (Forshaw, 2012). Hostility appears to be the main factor linked to heart disease and is a better predictor than the TAPB as a whole.

Type B Personality

The Type B personality is a psychological concept that describes individuals with a more relaxed, patient, and easygoing disposition compared to their Type A counterparts.

People with a Type B personality tend to exhibit flexibility, low competitiveness, and a relaxed, more laid-back approach to life. They are often more tolerant of others, adaptable to change, and less driven by time pressure.

Type B individuals generally experience lower levels of stress and may be perceived as more patient and less prone to aggression.

Individuals with Type B personalities work steadily, enjoying achievements, but do not become stressed when goals are not achieved.

People with Type B personalities tend to be more tolerant of others, are more relaxed than Type A individuals, are more reflective, experience lower levels of anxiety, and display a higher level of imagination and creativity.

Empirical Research

Friedman & Rosenman (1976) conducted a longitudinal study to test their hypothesis that Type A personality could predict incidents of heart disease. The Western Collaborative Group Study followed 3154 healthy men, aged between thirty-nine and fifty-nine for eight and a half years.

Participants were asked to complete a questionnaire. Examples of questions asked by Friedman and Rosenman:

- Do you feel guilty if you use spare time to relax?

- Do you need to win in order to derive enjoyment from games and sports?

- Do you generally move, walk and eat rapidly?

- Do you often try to do more than one thing at a time?

From their responses, and from their manner, each participant was put into one of two groups:

Type A behavior : competitive, ambitious, impatient, aggressive, fast talking.

Type B behavior : relaxed, non-competitive.

According to the results of the questionnaire, 1589 individuals were classified as Type A personalities, and 1565 Type B.

Findings

The researchers found that more than twice as many Type A people as Type B people developed coronary heart disease. When the figures were adjusted for smoking, lifestyle, etc. it still emerged that Type A people were nearly twice as likely to develop heart disease as Type B people.

For example, eight years later 257 of the participants had developed coronary heart disease. By the end of the study, 70% of the men who had developed coronary heart disease (CHD) were Type A personalities.

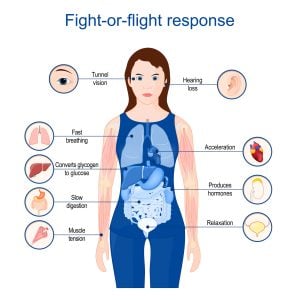

Type A personality types behavior makes them more prone to stress-related illnesses such as CHD, raised blood pressure, etc.

Such people are more likely to have their ” flight or fight ” response set off by things in their environment.

As a result, they are more likely to have the stress hormones present, which over a long period of time leads to a range of stress-related illnesses.

Research Evaluation

Limitations of the study involve problems with external validity. Because the study used an all-male sample, it is unknown if the results could be generalized to a female population, who have different ways to deal with stress and might be less vulnerable.

Studies carried out on women have not shown such a major difference between Type A and Type B and subsequent health. This may suggest that different coping strategies are just as important as personality.

The study was able to control for other important variables, such as smoking and lifestyle. This is good as it makes it less likely that such extraneous variables could confound the results of the study.

The study does not show which trait of personality type A leads to CHD. Matthew and Haynes (1996) found that hostility was most associated with CHD.

Dembroski et al. (1989) reanalyzed the results of the study and found that ratings on hostility were good predictors of CHD.

The participants of the original study were followed up by Carmelli (1991) and she found a very high rate of death caused by CHD in the participants with high hostility scores.

Theoretical Evaluation

However, there are several problems with the type A and B approach. Such approaches have been criticized for attempting to describe complex human experiences within narrowly defined parameters. Many people may not fit easily into a type A or B person. Also, in individualist cultures, men are socialized to display Type A behavior.

A longitudinal study carried out by Ragland and Brand (1988) found that as predicted by Friedman, Type A men were more likely to suffer from coronary heart disease. Interestingly, though, in a follow up to their study, they found that of the men who survived coronary events Type A men died at a rate much lower than type B men.

We are not sure type A or type B we tend to vary along the continuum depending on the circumstances and the situation we are in.

Some individuals with type A personalities are driven and well-balanced individuals unlikely to develop CHD, while some type Bs are in fact suppressing their hostility and their ambitions, these people are likely to develop CHD despite being classified as type B.

The major problem with the Type A and Type B theory is actually determining which factors are influencing coronary heart disease.

Some research (e.g., Johnston, 1993) has concentrated on hostility, arguing that the Type A behavior pattern is characterized by underlying hostility which is a major factor leading to coronary heart disease.

Other research has investigated the way that type A people experience and cope with stress, which is the major factor leading to coronary heart disease.

It would seem that a much more sophisticated model is needed to predict coronary heart disease than Friedman and Rosenman’s Type A & Type B approach. Indeed, personality type A could be the result of prolonged exposure stress.

References

Carmelli, D., Dame, A., Swan, G., & Rosenman, R. (1991). Long-term changes in Type A behavior: A 27-year follow-up of the Western Collaborative Group Study. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 14 (6), 593-606.

Dembroski, T. M., MacDougall, J. M., Costa, P. T., & Grandits, G. A. (1989). Components of hostility as predictors of sudden death and myocardial infarction in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Psychosomatic Medicine.

Forshaw, M., & Sheffield, D. (Eds.). (2012). Health psychology in action. John Wiley & Sons.

Johnston, D. W. (1993). The current status of the coronary prone behavior pattern. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 86(7), 406.

Ragland, D. R., & Brand, R. J. (1988). Coronary heart disease mortality in the Western Collaborative Group Study. Follow-up experience of 22 years. American Journal of Epidemiology, 127(3), 462-475.

Rosenman, R. H., Brand, R. J., Sholtz, R. I., & Friedman, M. (1976). Multivariate prediction of coronary heart disease during 8.5 year follow-up in the Western Collaborative Group Study. The American Journal of Cardiology, 37(6), 903-910.