On This Page:

A research hypothesis, in its plural form “hypotheses,” is a specific, testable prediction about the anticipated results of a study, established at its outset.

The research hypothesis is often referred to as the alternative hypothesis, or the “experimental hypothesis” in experimental research.

It typically suggests a potential relationship between two key variables: the independent variable, which the researcher manipulates, and the dependent variable, which is measured based on those changes.

For a hypothesis to be valid, it must be testable against empirical evidence, leading to its potential confirmation or refutation.

Types of Research Hypotheses

Alternative Hypothesis

The alternative hypothesis states a relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable has an effect on the other).

An experimental hypothesis predicts what change(s) will occur in the dependent variable when the independent variable is manipulated.

It states that the results are not due to chance and are significant in supporting the theory being investigated.

The alternative hypothesis can be directional, indicating a specific direction of the effect, or non-directional, suggesting a difference without specifying its nature. It’s what researchers aim to support or demonstrate through their study.

Null Hypothesis

The null hypothesis states no relationship exists between the two variables being studied (one variable does not affect the other). There will be no changes in the dependent variable due to manipulating the independent variable.

It states results are due to chance and are not significant in supporting the idea being investigated.

The null hypothesis, positing no effect or relationship, is a foundational contrast to the research hypothesis in scientific inquiry. It establishes a baseline for statistical testing, promoting objectivity by initiating research from a neutral stance.

Many statistical methods are tailored to test the null hypothesis, determining the likelihood of observed results if no true effect exists.

This dual-hypothesis approach provides clarity, ensuring that research intentions are explicit, and fosters consistency across scientific studies, enhancing the standardization and interpretability of research outcomes.

Nondirectional Hypothesis

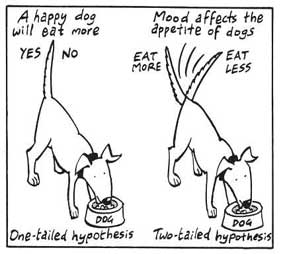

A non-directional hypothesis, also known as a two-tailed hypothesis, predicts that there is a difference or relationship between two variables but does not specify the direction of this relationship.

It merely indicates that a change or effect will occur without predicting which group will have higher or lower values.

For example, “There is a difference in performance between Group A and Group B” is a non-directional hypothesis.

Directional Hypothesis

A directional (one-tailed) hypothesis predicts the nature of the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. It predicts in which direction the change will take place. (i.e., greater, smaller, less, more)

It specifies whether one variable is greater, lesser, or different from another, rather than just indicating that there’s a difference without specifying its nature.

For example, “Exercise increases weight loss” is a directional hypothesis.

Falsifiability

The Falsification Principle, proposed by Karl Popper, is a way of demarcating science from non-science. It suggests that for a theory or hypothesis to be considered scientific, it must be testable and irrefutable.

Falsifiability emphasizes that scientific claims shouldn’t just be confirmable but should also have the potential to be proven wrong.

It means that there should exist some potential evidence or experiment that could prove the proposition false.

However many confirming instances exist for a theory, it only takes one counter observation to falsify it. For example, the hypothesis that “all swans are white,” can be falsified by observing a black swan.

For Popper, science should attempt to disprove a theory rather than attempt to continually provide evidence to support a research hypothesis.

Can a Hypothesis be Proven?

We can never 100% prove the alternative hypothesis. Instead, we see if we can disprove, or reject the null hypothesis.

If we reject the null hypothesis, this doesn’t mean that our alternative hypothesis is correct but does support the alternative/experimental hypothesis.

Upon analysis of the results, an alternative hypothesis can be rejected or supported, but it can never be proven to be correct.

We must avoid any reference to results proving a theory as this implies 100% certainty, and there is always a chance that evidence may exist which could refute a theory.

How to Write a Hypothesis

- Identify variables. The researcher manipulates the independent variable and the dependent variable is the measured outcome.

- Operationalized the variables being investigated. Operationalization of a hypothesis refers to the process of making the variables physically measurable or testable, e.g. if you are about to study aggression, you might count the number of punches given by participants.

- Decide on a direction for your prediction. If there is evidence in the literature to support a specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a directional (one-tailed) hypothesis. If there are limited or ambiguous findings in the literature regarding the effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable, write a non-directional (two-tailed) hypothesis.

- Make it Testable: Ensure your hypothesis can be tested through experimentation or observation. It should be possible to prove it false (principle of falsifiability).

- Clear & concise language. A strong hypothesis is concise (typically one to two sentences long), and formulated using clear and straightforward language, ensuring it’s easily understood and testable.

Examples

Consider a hypothesis many teachers might subscribe to: students work better on Monday morning than on Friday afternoon (IV=Day, DV= Standard of work).

Now, if we decide to study this by giving the same group of students a lesson on a Monday morning and a Friday afternoon and then measuring their immediate recall of the material covered in each session, we would end up with the following:

- The alternative hypothesis states that students will recall significantly more information on a Monday morning than on a Friday afternoon.

- The null hypothesis states that there will be no significant difference in the amount recalled on a Monday morning compared to a Friday afternoon. Any difference will be due to chance or confounding factors.

More Examples

- Memory: Participants exposed to classical music during study sessions will recall more items from a list than those who studied in silence.

- Social Psychology: Individuals who frequently engage in social media use will report higher levels of perceived social isolation compared to those who use it infrequently.

- Developmental Psychology: Children who engage in regular imaginative play have better problem-solving skills than those who don’t.

- Clinical Psychology: Cognitive-behavioral therapy will be more effective in reducing symptoms of anxiety over a 6-month period compared to traditional talk therapy.

- Cognitive Psychology: Individuals who multitask between various electronic devices will have shorter attention spans on focused tasks than those who single-task.

- Health Psychology: Patients who practice mindfulness meditation will experience lower levels of chronic pain compared to those who don’t meditate.

- Organizational Psychology: Employees in open-plan offices will report higher levels of stress than those in private offices.

- Behavioral Psychology: Rats rewarded with food after pressing a lever will press it more frequently than rats who receive no reward.