On This Page:

The term MMPI in personality assessment refers to the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. This standardized psychometric test identifies personal, social, and behavioral issues in psychiatric patients.

Key Takeaways

- The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is a psychological instrument to assess personality traits and different forms of psychopathology.

- It is administered by a trained psychologist or mental health professional who relies upon ten clinical scales to diagnose a patient with mental health or other clinical issues.

- Since it was first developed in 1939 by Starke Hathaway and J.C. McKinley, several versions have been revised, including one for adolescents.

- This test currently has two versions in operation, the original being the MMPI which was developed during the 1940s and is still in use. It contains 550 true/false items. The second version is the MMPI-2 which was introduced in 1990 and contained around 567 items.

- The clinical and validity scales are the two key scales clinicians use when administering the MMPI. However, there is also a content scale to help provide insight into specific types of symptoms and many other supplemental scales to help increase the validity of this tool.

- The MMPI-2 is one of the most widely used psychological tools – from treatment plans and the hiring process to law enforcement and marital counseling. Nevertheless, it does not come without its criticisms. Scholars have observed unfair racial disparities in scoring the test, and others argue that some of the scales are not scientifically valid.

History of the MMPI

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is probably the most widely used multidimensional tool to help diagnose mental health disorders. This test was first developed in 1939 by clinical psychologist Starke Hathaway and neuropsychiatrist J.C. McKinley at the University of Minnesota, and it was first published in 1943.

Because this tool is unique in that it is created to measure psychopathology specifically, as opposed to simply assessing anyone’s personality, in order to develop the instrument, the team constructed clinical scales that were endorsed by patients who had been diagnosed with certain mental disorders (Hathaway & McKinley, 1940).

Unlike other personality tests, the MMPI was not based on any particular prevailing theories about personality, such as the five-factor model or 16 personalities. It simply measures where an individual falls on 10 different mental health scales in order to diagnose the patient and get them the proper treatment they need.

This test currently has two versions in operation, the original being the MMPI which was developed during the 1940s and is still in use.

The MMPI developed from hundreds of true/false questions that were felt would be useful in identifying personality dimensions. These questions were then given to people suffering from a variety of psychological disorders and to a group that did not suffer from any disorder.

They then identified the questions that most people suffering from a particular type of illness answered differently from those who were identified as normal. Consequently, if a person tended to answer many of the questions in the way in which paranoid people answered, it was highly likely that the individual was also paranoid.

How the Test Has Changed

Although this atheoretical approach allowed the MMPI to meaningfully capture traits that were directly related to psychopathology, the initial version was widely criticized.

Specifically, many scholars pointed to the fact that the original control group had a very small sample size and was primarily composed of young, white, and married people from the rural Midwest.

Additionally, the MMPI was attacked for using incorrect terminology and not including a wide enough range of mental health issues, such as suicidal tendencies and drug abuse (Gregory, 2004).

As a result, the MMPI went through multiple stages of revision.

MMPI-2

In 1989, the first major revision of this tool occurred, producing the MMPI-2. To address the concern that the initial inventory was not tested on a representative sample, the MMPI-2 was standardized based on 2,600 individuals who were from more diverse backgrounds (Gregory, 2004).

Additionally, some of the items on the test were revised and some sub-scales were introduced to better help the clinicians administering the MMPI interpret the results.

The MMPI-2 is meant for adults and contains 576 true/false items that typically take around one to two hours to complete.

It is designed for all adults over the age of 18 and requires a sixth-grade reading level (Gregory, 2004).

Although this specific test isn’t made for those who are younger than 18, an adolescent version of the MMPI has also been created.

MMPI-A

A couple of years after the MMPI-2 was released, the MMPI-A (A for adolescents) was developed to include individuals aged 14 to 18.

After empirical testing revealed that 12 and 13-year-olds could not sufficiently understand the questions, 14 was deemed the cutoff for this personality inventory.

To this day, there is still no version for children younger than 14. The MMPI-A contains 478 items, and adolescents are scored along the same 10 scales that are used for the MMPI-2 (Kaemmer, 1992).

But why does there need to be a separate MMPI for adolescents? Doesn’t the one for adults suffice?

Although the MMPI-A very closely resembles the adult version of this personality test, clinicians were concerned that there was inadequate content on the MMPI-2 (the adult version) and that the items did not cover content relevant enough to adolescents, such as items addressing relations with peers or school.

They also feared that there was a lack of appropriate norms which are necessary for addressing how an individual might be deviating from such norms.

Adolescence is a critical period of development, so the norms for how a 14-year-old is expected to act would not be the same as an adult whose brain is finished maturing.

When trying to decide whether to use adult norms that highly pathologized children or recently-published adolescent norms which hadn’t been extensively reviewed, psychologists could not even reach a consensus.

Thus, it made sense to create a completely separate version of the MMPI for this population (Kaemmer, 1992).

To test the new MMPI-A and establish new norms, psychologists recruited 1,620 individuals for the normative sample and 713 individuals for the clinical sample.

This new version was praised for including more relevant item content, being shorter, and having a high degree of validity (Kaemmer, 1992).

The MMPI-A resembles the MMPI-2 in many ways, one being that it, too, continues to be criticized.

One of the major criticisms is that the clinical sample used to establish the norms was not a representative sample. All of the individuals were in treatment facilities in Minneapolis, Minnesota, so it did not reflect geographic areas around the globe.

Additionally, scholars argue that there is too much overlap across the 10 different clinical scales and that even though it is shorter compared to the original MMPI, it is still too long and advanced for adolescents (Whitcomb & Merrell, 2013). As a result, a new scale was established.

MMPI-2 RF

Ideas and theories are constantly evolving, and there are always ways to improve upon methodological flaws in the research design.

The research world is an endless cycle of testing, publishing, receiving critiques, and retesting. And the development of the MMPI followed this same pattern. After both the MMPI-2 and the MMPI-A received backlash from the academic community, both received revisions.

The MMPI-2 RF (restructured form) was published in 2008, inspired by a restructuring of the ten clinical scales that was done in 2003 (Tellegen et al., 2003).

This new version has been extensively tested in the empirical setting and is able to differentiate between different clinical symptoms and broader diagnoses.

It only has 338 questions, significantly fewer than the MMPI-2, and takes around 35-50 minutes to complete.

MMPI-A RF

The MMPI-A RF was first published in 2016 and sought to address the many criticisms that the original adolescent multiphasic inventory received.

Namely, it only contains 241 true-false items – less than half the number of items of the original MMPI-A to help combat the challenges of adolescent attention span and concentration.

Additionally, this version tries to do a better job of increasing discriminant validity, which occurs when non-overlapping factors do, in fact, not overlap (Handel, 2016).

The MMPI-A RF is one of the most commonly used psychological tools among the adolescent population (Whitcomb & Merrell, 2013).

MMPI-2

In 1989, the first major revision of this tool occurred, producing the MMPI-2. To address the concern that the initial inventory was not tested on a representative sample, the MMPI-2 was standardized based on 2,600 individuals who were from more diverse backgrounds (Gregory, 2004).

Additionally, some of the items on the test were revised and some sub-scales were introduced to better help the clinicians administering the MMPI interpret the results.

The MMPI-2 is meant for adults and contains 576 true/false items that typically take around one to two hours to complete. It is designed for all adults over the age of 18 and requires a sixth-grade reading level (Gregory, 2004).

Although this specific test isn’t made for those who are younger than 18, an adolescent version of the MMPI has also been created.

Administration

The MMPI-2 includes a restandardization of the test, which includes 567 items and takes approximately 60 to 90 minutes to complete. Like the MMPI, the updated version has 10 clinical scales with each scale having approximately 32 to 78 items each.

The vast majority of people obtain a few scores on each scale. However, those administering the test are looking for a higher-than-average score on a scale to indicate a potential problem.

Additionally, the MMPI is copyrighted by the University of Minnesota, which means clinicians must pay to administer and utilize the test.

There are multiple different reasons for administering the MMPI. A clinician will typically decide to administer this test to help develop treatment plans for a patient and assist with differential diagnosis.

It can also be used as part of the therapeutic assessment procedure or to help answer legal questions (Butcher & Williams, 2009).

Another common usage for the MMPI is to screen job candidates during the personnel selection process, where applicants are vetted, especially in careers such as law enforcement.

The MMPI may also be used during college, career, and marital counseling, as well as in child custody disputes and substance abuse programs (Ben-Porath & Tellegen, 2008).

The MMPI can only be administered and interpreted by psychologists who have been extensively trained in it. When it is being administered by these clinicians, however, it can be done so online or with a physical booklet.

After a participant takes the test, an evaluator will make an interpretative report based on their responses.

The scores will then be converted into what are called normalized T scores, ranging from 30-120. The normal range is from 50-65, and anything outside of this range is marked as clinically significant (Framingham, 2016).

Over time, a set of standard clinical profiles, or “codetypes,” have emerged. A codetype is when two clinical scales have high T scores.

For example, a 2-7 codetype means that a participant scored high on both scale 2 (depression) and scale 7 (psychasthenia or OCD), demonstrating signs of depression and anxiety. There are numerous common codetypes that have been identified and are understood by the clinician population.

It is important to note that the MMPI-2 is not administered in a vacuum. A participant’s background is taken into account, and this test is typically not the only evaluative tool that will be given to a person. Nevertheless, the MMPI-2 itself is an incredibly valuable tool for identifying psychopathology in people around the world.

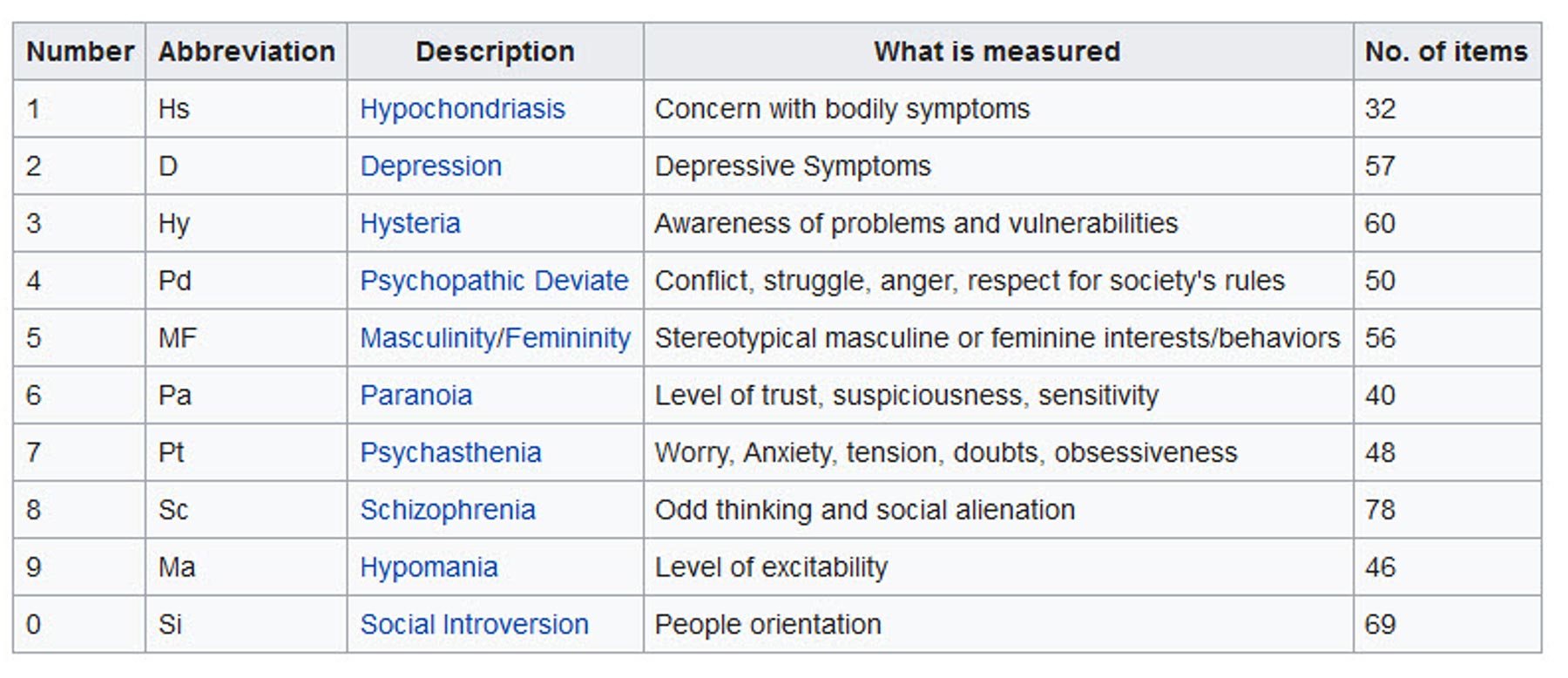

10 Clinical Scales

The MMPI is designed to evaluate the thoughts, feelings, attitudes, and behaviors that make up an individual’s personality.

The test is administered by a trained clinician, typically a psychologist or psychiatrist, who relies on a series of clinical scales to interpret the results (Framingham, 2016).

These clinical scales help illustrate certain forms of psychopathology that an individual may have. The 10 clinical scales are as follows:

- Hypochondriasis (Hs): The Hypochondriasis scale encompasses anything related to complaints about body functioning. These complaints are typically focused on the back and abdomen and persist even when medical tests are negative or inconclusive. A high score on this scale could indicate that worrying about your health interferes with your life and could greatly impact your relationships with others. This scale contains 32 items.

- Depression (D): The Depression scale evaluates whether an individual has clinical depression, which is marked by low morale, lack of hope in the future, a disinterest in previously-enjoyed activities, feelings of worthlessness, difficulties with attention, and overall dissatisfaction with life. This scale has 57 unique items.

- Hysteria (Hy): The Hysteria scale examines five different components – poor physical health, shyness, cynicism, headaches, and neuroticism. Put simply, it measures an individual’s response to stress – both physical and mental symptoms. It contains 60 items.

- Psychopathic Deviate (Pd): The Psychopathic Deviate scale records general social maladjustment in addition to an absence of strongly pleasant experiences. The specific items investigate complaints about family and authority figures, self and social alienation, and boredom. This scale tries to get at whether you are experiencing antisocial behaviors. If you score high, you may be diagnosed with a personality disorder. This scale contains 50 items.

- Masculinity/Femininity (Mf): The Masculinity/Femininity scale surveys an in individual’s interests, hobbies, aesthetic preferences, and personal sensitivity. It tries to understand how closely a person conforms to traditionally stereotyped masculine and feminine roles. This scale has 56 items.

- Paranoia (Pa): The Paranoia scale looks at interpersonal sensitivity, moral self-righteousness, and suspiciousness. There are 40 items total, some of which are psychotic symptoms, acknowledging the existence of paranoid and delusional thoughts and beliefs, extreme suspicion of other people, grandiose thinking, and feelings of being persecuted by society.

- Psychasthenia (Pt): The Psychasthenia scale seeks to measure a person’s inability to resist certain thoughts or actions. Psychasthenia is an outdated term used to describe what is called obsessive-compulsive order (OCD) today. This scale observes compulsive behaviors, abnormal fears, self-criticisms, difficulties in concentration, anxiety, and guilt feelings. It has 48 items overall.

- Schizophrenia (Sc): The Schizophrenia scale examines whether a person experiences hallucinations and delusions and is likely to develop schizophrenia. Specifically, it measures whether the patient has bizarre thoughts, peculiar perceptions, poor familial relationships, difficulties in concentration, impulse control, lack of deep interests, questions of self-worth, sexual difficulties, and experiences of social alienation. This scale has the greatest number of items at 78.

- Hypomania (Ma): The Hypomania scale seeks to evaluate degrees of excitement, marked by an elated yet unstable mood, psychomotor excitement, such as shaky hands, and a string of never-ending ideas. This dimension looks at both behavioral and cognitive overactivity, grandiosity, impulsivity, rapid speech, irritability, and egocentricity. It contains a total of 46 items.

- Social Introversion (Si): The final scale, the Social Introversion scale, measures the social introversion and extroversion of a person. Social introverts may choose to avoid social interactions and prefer to be alone or with a small group of friends. This scale looks at degrees of competitiveness, compliance, timidity, and dependence. This last scale has 69 items.

Together, these 10 dimensions comprise the clinical scales of the MMPI. Although there are many supplementary scales, these are the main 10 that guide a clinician’s evaluation of an individual. However, to accompany these 10 scales, a series of validity scales are also used to ensure the accuracy of the results.

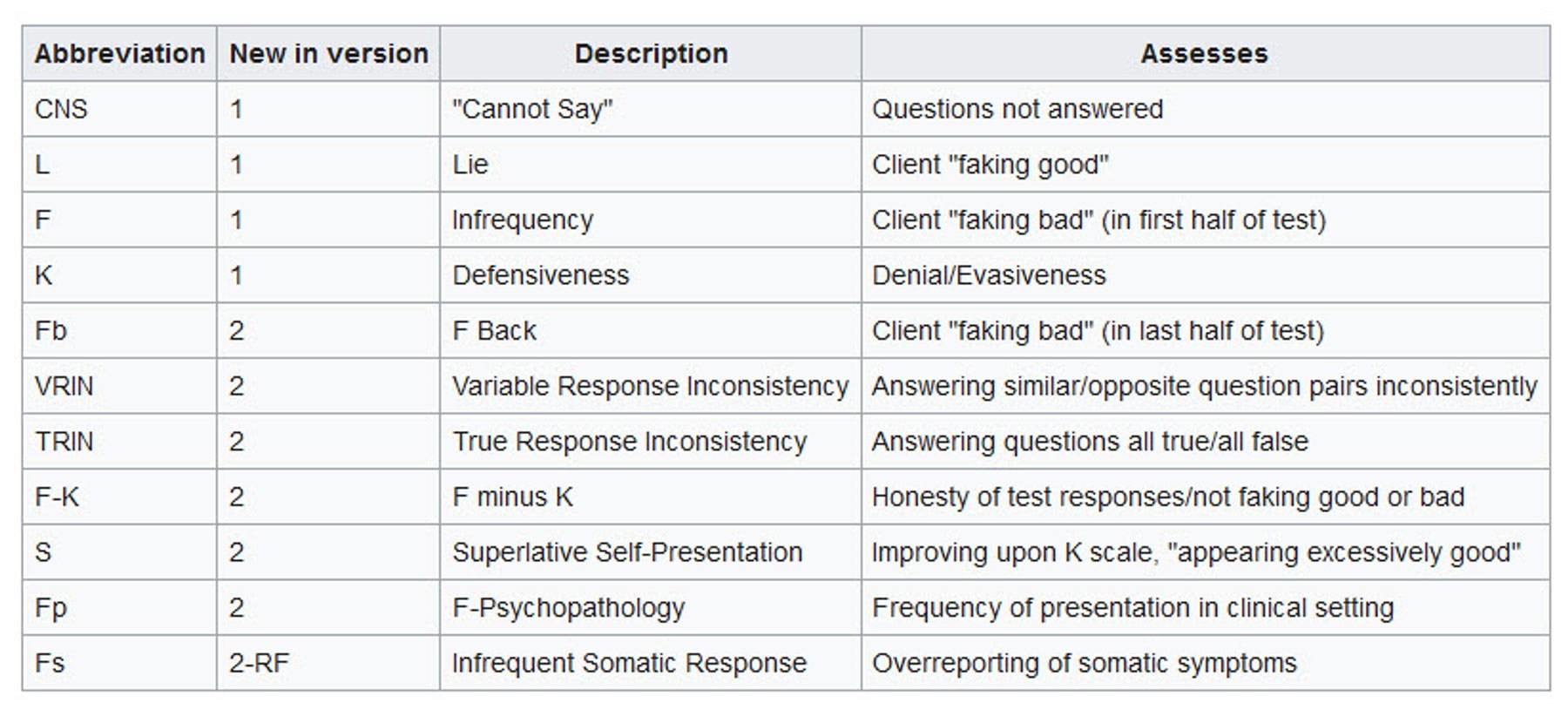

Validity Scales

Validity refers to how accurately a method is actually measuring what it intends to measure. A common analogy for validity involves a dart board.

If all of the arrows are close to the bullseye, that is an example of strong validity because all of the arrows are close to what they are supposed to be close to. Even if some are slightly too high and some are slightly too low, if all of the arrows are close to the middle, that indicates high validity.

For the MMPI, there are not only studies that investigate the validity of the MMPI as a tool, but the instrument itself has its own validity scales to ensure that the test taker’s answers aren’t over-reported, under-reported, or flat out dishonest. In other words, the following scales help ensure that the respondent’s answers reflect what they should actually be reflecting (Framingham, 2016):

- Lie (L): The Lie scale aims to identify individuals who are intentionally trying to lie on the MMPI items. The scale measures general attitudes that are culturally admirable but highly uncommon as a way of testing whether respondents are deliberately trying to elevate their status and make themselves look like a better person than they actually are. This scale contains 15 items.

- F: The F scale attempts to detect abnormal ways of answering each of the test items (for example, if a person were intentionally randomly answering the questions on the test). It tries to understand whether a participant has strange thoughts, peculiar experiences, feelings of alienation, and a variety of other unlikely beliefs and expectations. The items are scattered throughout the entire test up until item 360, so as to not make it obvious that these items are not part of the clinical portion of the test. This scale contains 60 items.

- Back F (Fb): The Back R scale is the same as the F scale but these items are scattered throughout the latter half of the test. It tries to measure if you’ve become fatigued, distressed, or distracted in a way that affects the validity of your responses. This scale has 40 items.

- K: The K scale seeks to help identify psychopathology in those who would have otherwise been labeled as normal. It measures self-control, family and interpersonal relationships, and defensiveness. Along with the L scale, this scale helps illuminate a person’s need to be seen positively. This scale is composed of 30 items.

- CNS: The CNS (Cannot Say) scale evaluates how often a person doesn’t answer an item on the test. A test with more than 30 unanswered questions may be invalidated.

- TRIN and VRIN: The TRIN (True Response Inconsistency) and VRIN (Varied Response Inconsistency) scales identify where the test taker chose answers without actually considering the question. In a TRIN pattern, the respondent might mark 10 true followed by 10 false responses in a row, an unlikely response pattern that warrants further observation. The VRIN pattern reveals a random pattern of true/false responses.

- Fp: The Fp scale tries to reveal whether the participant is intentionally or unintentionally over-reporting, which may reflect a mental health disorder. This scale has 27 items.

- FBS: The FBS scale, also known as the Fake Bad Scale or the symptom validity scale, is designed to measure the intentional over-reporting of symptoms specifically. This scale has 43 items.

- S: The S scale (also known as the Superlative Self-Presentation scale) observes how you answer 50 questions about serenity, contentment, morality, human goodness, and patience, again to see if you are reporting answers in such a way that makes you look like a better person. If you underreport in 44 of the 50 questions, you might feel like you have to be defensive.

Empirical Studies Validating MMPI

As mentioned, high validity occurs when a tool measures what it claims to be measuring. So, in the case of the MMPI, high validity means that this inventory is actually measuring different types of psychopathology as it claims to be.

In other words, if someone actually has depression and was diagnosed with depression through other means, the MMPI would be deemed valid if it also revealed depressive traits in an individual.

Conveniently, the level of validity can be determined by the empirical world. Several research studies have sought to examine the degree to which the MMPI is actually a valid tool.

Specifically, a 1999 meta-analysis compared the validity of the MMPI with the Rorschach inkblot test, finding very similar validity coefficients for both. A validity coefficient is a way of quantifying a test’s validity and ranges from 0-0.5, and anything that falls between 0.21-0.35 is labeled as likely to be useful. The validity coefficient was 0.3 for the MMPI and 0.29 for the Rorschach test.

Additionally, when broken down further, the researchers found that the MMPI had larger validity coefficients for studies using psychiatric diagnoses and self-report measures, but the Rorschach had higher validity coefficients for studies that used objective criterion variables (Hiller et al., 1999).

Another study measured the extent to which the MMPI can discriminate between sex offenders and controls. In the study, 479 men took the MMPI and were scored on scales measuring sexual behavior and deviance, substance abuse, personality, violence, and more.

The examination of these scales revealed that the MMPI could help to screen sex offenders at a rate that is better than chance, demonstrating that this is a valid tool for correctly identifying sex offenders (Langevin et al., 1990).

Validity studies don’t only measure the MMPI in general, but some studies measure the validity of the validity scales themselves. For example, one study looked at the validity of the FBS scale which is used to identify individuals who are over-reporting somatic symptoms.

The researchers measured associations between scores on the MMPI-FBS scale and a symptom validity test (SVT) in 127 criminal defendants and 141 civil claimants. The researchers found that scores on the FBS were, in fact, associated with SVT failure (incorrectly reporting symptoms) in both the criminal and civil defendants (Wygant et al., 2007).

This study helps support the utility of the FBS as an indicator of inaccurate reporting of both somatic and cognitive complaints.

Another study observed the validity of the F and Fp scales in detecting psychopathology in a criminal forensic setting.

One hundred twenty-five criminal defendants were given a Structured Interview of Reported Symptoms (SIRS) and the MMPI-2 RF. The results revealed that the two MMPI-2 RF scales created to detect over-reported psychopathology were able to properly differentiate between those who were actually ill and those who were faking it, supporting the validity of these scales (Sellbom et al., 2010).

Together, these studies help to demonstrate that the MMPI-2 is a valid test. Not only does it have validity scales in place, but these scales themselves are valid too.

Having this kind of confirmation allows this tool to be viewed as highly credible and effective by the research world.

Empirical Research

Research on the MMPI-2 extends beyond its validity. Several research studies have examined this tool in various settings and with different populations. One study relied on the MMPI-2 for identifying key disorders among battered women in transition.

Of the 31 women who were evaluated, 90% scored high on the psychopathy, paranoia, and schizophrenia scales (Khan et al., 1993). This study demonstrates how the MMPI-2 can be used in the clinical setting to not only help diagnose but to then help identify proper intervention strategies once an individual’s symptoms are identified.

And because these symptoms were so universally prevalent, it helps clinicians target treatment approaches among a wider population.

Another population that has been targeted is college students.

Specifically, one study administered the MMPI-2 to 515 male and 797 female college students from four different universities. The researchers found that college students respond to the MMPI-2 in a very similar manner to the normative sample (Butcher et al., 1990).

This helped to demonstrate that the MMPI-2 norms are appropriate for college participants.

One notable setting in which the MMPI-2 has been studied is the workplace. Bullying at work, defined as exposure to psychological violence and harassment, can place an unnecessary strain on employees and greatly affect their productivity.

The study attempted to use the MMPI-2 to identify psychological correlates of bullying among 85 former and current victims. The researchers found that bullied victims had an elevated personality profile on the MMPI-2 and that the personality profiles of the victims were directly related to the type and intensity of behaviors the victim experienced (Matthiesen & Einarsen, 2001).

These are just a couple of examples that serve to demonstrate the expansive literature on the MMPI-2. Researchers target varying populations, settings, and even versions of this test.

Critical Evaluation

Although it is clear that the MMPI-2 is a widely used and highly valid test, it does not come without its criticisms.

One major criticism is racial disparity (McCreary & Padilla, 1977).

Scholars have recognized a difference between whites and non-whites in scoring, whereby non-white individuals receive an average of 5 points higher, putting them closer to a diagnosis than their white counterparts.

Studies done in divergent populations such as incarcerated people, medical patients, and high school students have found that Black respondents usually score higher than whites on many of the scales.

However, researchers note that there is not a higher level of psychopathology among racial and ethnic minorities, pointing to flaws in the test design as an explanation for this disparity instead.

Another main criticism relates to the validity of the FBS scale. Butcher and colleagues (2008) argue that is not actually measuring the degree to which participants are over-reporting their symptoms.

They also claim that this scale has the potential for bias against women, those with disabilities and physical illness, psychiatric inpatients, and those exposed to traumatic situations.

Finally, they note that the criteria used to define malingering (exaggerating or feigning illness) is not replicable.

In a separate paper, the same researchers argued that the MMPI-2 RF is not a viable replacement for the MMPI-2 in certain crucial evaluations, such as when dealing with child custody cases (Butcher & Williams, 2012).

However, there is a lot of pushback from the scientific community on Butcher and Williams’ critique, arguing that it is misleading and that the examples the researchers include are cherry-picked.

In general, the MMPI-2 is widely accepted by the scientific community, as reflected by its popularity.

FAQs

How many different scales are used to compile a profile from the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI)?

The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) uses 10 clinical scales to compile a profile. However, in its latest version, MMPI-2-RF, there are 50 scales, including validity, substantive, and supplementary, to provide more detailed personality and psychopathology assessments.

What is one main difference between the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory (MMPI) and the Rorschach inkblot test?

One main difference is that the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is a self-report inventory with specific, structured questions, while the Rorschach Inkblot Test is a projective test where individuals interpret ambiguous inkblots, revealing unconscious desires and conflicts.

What is the purpose of the MMPI?

The purpose of the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) is to assess and measure various aspects of an individual’s personality, mental health, and psychopathology, providing valuable insights for clinical diagnosis, treatment planning, and research in fields such as psychology, psychiatry, and counseling.

References

Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2012). Interpreting the MMPI-2-RF. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ben-Porath, Y. S., & Tellegen, A. (2008/2011). MMPI-2-RF (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form) manual for administration, scoring, and interpretation. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Ben-Porath, Y. S., & Tellegen, A. (2008). Empirical correlates of the MMPI–2 Restructured Clinical (RC) scales in mental health, forensic, and nonclinical settings: An Introduction. Journal of Personality Assessment, 90(2), 119-121.

Briggs-Myers, I., & Myers, P. B. (1995). Gifts differing: Understanding personality type.

Butcher, J. N., Gass, C. S., Cumella, E., Kally, Z., & Williams, C. L. (2008). Potential for bias in MMPI-2 assessments using the Fake Bad Scale (FBS). Psychological Injury and Law, 1(3), 191-209.

Butcher, J. N., Graham, J. R., Dahlstrom, W. G., & Bowman, E. (1990). The MMPI-2 with college students. Journal of Personality Assessment, 54(1-2), 1-15.

Butcher, J. N., & Williams, C. L. (2009). Personality assessment with the MMPI‐2: Historical roots, international adaptations, and current challenges. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 1(1), 105-135.

Butcher, J. N., & Williams, C. L. (2012). Problems with using the MMPI–2–RF in forensic evaluations: A clarification to Ellis. Journal of Child Custody, 9(4), 217-222.

Framingham, J. (2016). Minnesota Multiphasic personality Inventory (MMPI). Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/lib/minnesota-multiphasic-personality-inventory-mmpi#What-Does-the-MMPI-2-Test?

Gregory, R. J. (2004). Psychological testing: History, principles, and applications. Allyn & Bacon.

Handel, R. W. (2016). An introduction to the Minnesota multiphasic personality inventory-adolescent-restructured form (MMPI-A-RF). Journal of clinical psychology in medical settings, 23(4), 361-373.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1940). A multiphasic personality schedule (Minnesota): I. Construction of the schedule. The Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 249-254.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley J. C. (1942). Manual for the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Hathaway, S. R., & McKinley, J. C. (1943). The MMPI. Minneapolis.

Hiller, J. B., Rosenthal, R., Bornstein, R. F., Berry, D. T., & Brunell-Neuleib, S. (1999). A comparative meta-analysis of Rorschach and MMPI validity. Psychological Assessment, 11(3), 278.

Kaemmer, B. (1992). Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-Adolescent Version (MMPI-A): Manual for administration, scoring and interpretation.

Khan, F. I., Welch, T. L., & Zillmer, E. A. (1993). MMPI-2 profiles of battered women in transition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 60(1), 100-111.

Langevin, R., Wright, P., & Handy, L. (1990). Use of the MMPI and its derived scales with sex offenders: I. Reliability and validity studies. Annals of Sex Research, 3(3), 245-291.

Matthiesen, S. B., & Einarsen, S. (2001). MMPI-2 configurations among victims of bullying at work. European Journal of work and organizational Psychology, 10(4), 467-484.

Sellbom, M., Toomey, J. A., Wygant, D. B., Kucharski, L. T., & Duncan, S. (2010). Utility of the MMPI–2-RF (Restructured Form) validity scales in detecting malingering in a criminal forensic setting: A known-groups design. Psychological Assessment, 22(1), 22.

McCreary, C., & Padilla, E. (1977). MMPI differences among black, Mexican‐American, and white male offenders. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 33(S1), 171-177.

Tellegen, A., Ben-Porath, Y. S., McNulty, J. L., Arbisi, P. A., Graham, J. R., & Kaemmer, B. (2003). MMPI-2 Restructured Clinical (RC) scales: Development, validation, and interpretation.

Tellegen, A., & Ben-Porath, Y. S. (2008/2011). MMPI-2-RF (Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2 Restructured Form) technical manual. Minneapolis. University of Minnesota Press.

Tupes, E. C., & Christal, R. E. (1992). Recurrent personality factors based on trait ratings. Journal of personality, 60(2), 225-251.

Whitcomb, S., & Merrell, K. W. (2013). Behavioral, social, and emotional assessment of children and adolescents. Routledge.

Wygant, D. B., Sellbom, M., Ben-Porath, Y. S., Stafford, K. P., Freeman, D. B., & Heilbronner, R. L. (2007). The relation between symptom validity testing and MMPI-2 scores as a function of forensic evaluation context. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 22(4), 489-499.

Further Reading

- Interpretation of MMPI-2 Clinical Scales. MMPI-2 Training Slides, Univerity of Minnesota Press; 2015.

- Interpretation of MMPI-2 Validity Scales. MMPI-2 Training Slides, Univerity of Minnesota Press; 2015.

- Ben-Porath YS, Tellegen A. MMPI-3: Manual for Administration, Scoring, and Interpretation. Pearson; 2020.

- Floyd AE, Gupta V. Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Updated May 1, 2021.